As you may know, Fort Ti has been in a bit of a publicity war caused by people who don't like that the interpretive guidelines have been tightened up and there's a "new Sheriff in town." Ward Oles (www.attheeasterndoor.com) brought to my attention some letters written to a local newspaper (Times of Ti).

http://www.timesofti.com/news/2011/sep/14/re-enactors-upset-fort-ti/

Here is mine:

Dear Susan,

There has been a conflict brewing for the last couple of years at Fort Ti. It is not a battle like the Fort is used to. No cannon fire or volleys of muskets. This is a cultural conflict.

On one side (group 1), we have re-enactors/living historians who strive to present an image to the public and to their fellow participants that is as close as possible to their chosen 18th century persona. These folks spend countless hours poring over journals, trade lists, woodcuts, etc to find all the available information on any given subject. Whether it be an $1800 firearm or a $20 shoe buckle, they want it to be the right one. Their camps are usually pretty Spartan as this is what their research has shown the original camps were.

On the other side (group 2), things are different. We have folks for whom "good enough" is the criteria. They use outdated information, or just outright hearsay to base their persona on. Their camps are usually set up like backyard BBQs with huge amounts of chairs, tables, cookware, etc.

But the biggest difference shows in their attitudes towards the sites they frequent. Group #1 realizes that it is a PRIVLEGE to walk onto private property, set up a tent or lean-to, make a fire to cook/heat with and run around with a flintlock.

For group #2, it is there "right" to be at Fort Ti's events. They "have been coming here since..." is usually their argument. They don't care about the public getting a small glimpse of the period in question. They care about having fun. Their motivation is to have a costume party. Now that the focus is on getting people to take things more seriously, they have started a campaign of misinformation hoping to get "their fort" back. They figure if they spread enough rumors, falsehoods and outright lies, people will not show up and the Fort will be forced to allow them back and go back to "the good old days". One of them even went so far as to run a fake ad in a well-known Living History newspaper to try and sabotage the June F&I event.

These are the people you will hear stating that the Fort is being ruined.

Group 1 has invited Group 2 along for the ride. It's offered to help them along in doing a better public interpretation. Group 2 has generally declined harshly (a few have taken up the challenge).

The times are changing. Things are improving. The Fort is not dying. People need to learn to deal with it and hop on with the rest of the team.

Mario Doreste

Sharon Springs, NY

If you'd like to send a letter, please do so to this email addy: susan@denpubs.com

By Canoe and Snowshoe

Bienvenue!!

This is a journal of my personal experiences in the research of 17th & 18th methods for wilderness living and travel. My main interests are canadiens (especially those involved in the fur trade) and First Nations people of the North during this period.

It's also the home page for the Company of Voyageurs and Hivernants, a small Living History unit that gives demos at various historical sites.

“I would hold back all the voyageurs and employees of the Far West, gaining two thousand excellent men.” Bougainville, September 1758

This is a journal of my personal experiences in the research of 17th & 18th methods for wilderness living and travel. My main interests are canadiens (especially those involved in the fur trade) and First Nations people of the North during this period.

It's also the home page for the Company of Voyageurs and Hivernants, a small Living History unit that gives demos at various historical sites.

“I would hold back all the voyageurs and employees of the Far West, gaining two thousand excellent men.” Bougainville, September 1758

Friday, September 16, 2011

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

“When the French are traveling about in the country…”: The Canadien on the trail

Most folks who know me in person know I've been working on a book about Canadien milice for a while now. Kind of a supplement to Steve Delisle's book. Here's a rough draft of a chapter I haven't finished yet, just as a taste:

While researching Canadien milice (militia) and the Fur Trade during the 17th and 18th centuries, one thing is quite evident. The French-Canadian was on much better terms with his red-skinned neighbors than the English settler to the south. One big factor was the difference in philosophy. The English, by and large, came to the New World to settle, grow crops and harvest timber, etc. They sought ownership of land. The French had minimal settlement. They were after furs and cod to send home more than anything else, keeping only as many settlers as needed to support these 2 industries.

Swedish scientist Peter Kalm traveled to New York and New France in the late 1740s. His journals are invaluable to the modern living historian. For students of 18th century New France, Kalm’s journals give us a glimpse of life among the upper class as well as commoner. For my purposes, the descriptions of the average Canadien at home and in travels in the forest are the focus.

Kalm mentions on multiple occasions the similarities in dress between the French and the Indians:

"Though many nations imitate the French customs, I observed on the contrary, that the French in Canada in many respects follow the customs of the Indians, with whom they have constant relations. They use the tobacco pipes, shoes, garters, and girdles of the Indians. They follow the Indian way of waging war exactly; they mix the same things with tobacco; they make use of the Indian bark boats and row them in the Indian way; they wrap a square piece of cloth around their feet [as a moccasin liner], instead of stockings, and have adopted many Indian fashions.” (Kalm, page 511)

“During the week the men went about in their homes dressed much like the Indians, namely, in stockings and shoes like theirs, with garters, and a girdle about the waist; otherwise the clothing was like that of other Frenchmen.” (Kalm, page 558)

“From the skins of these animals [deer] the natives as well as the French in -Canada make their shoes which they use on their journeys…” (Kalm, page 589)

The wearing of breechcloth and leggings was not just an 18th century phenomenon. The coureur de bois had figured out the advantages to this form of dress many years before:

“They [the CdB] easily adopt Indian fashions. They run the woods with leggings and moccasins and instead of breeches they wear only a breechclout.” (H. de Tonty, Dernieres decouverts dans l’Amerique Septentrionale de M. de La Salle, Paris, 1697. Page 14)

Gov. Denonville wrote of woodsmen who “put themselves in Indian Dress” in 1685. (Archives Nationales de Canada, C11A, volume 7, folio 90)

By the middle of the next century, Indian dress was the norm for the Canadien in the forest.

“When the French are traveling about in this country, they are generally dressed like the natives; they wear no trousers…” (Kalm Page 560)

The term “Indian Dress” in the 18th century generally meant shirt, breechcloth and leggings. It is a simple, inexpensive dress (even today!) that afforded relative comfort and freedom of movement. Even George Washington saw its merits.

“I wou'd not only order the Men to adopt the Indian dress, but cause the Officers to do it also, and be the first to set the example myself. Nothing but the uncertainty of its taking with the General causes me to hesitate a moment at leaving my Regimentals at this place, and proceeding as light as any Indian in the Woods. 'Tis an unbecoming dress, I confess, for an officer; but convenience rather than shew, I think shou'd be consulted. The reduction of Bat Horses alone, is sufficient to recommend it; for nothing is more certain than that less baggage will be requir'd, and that the Publick will be benifitted in proportion." (Washington to Col. Bouquet; Camp near Fort Cumberland, July 3, 1758.)

“…therefore myself and others gave up our horses for Packs, to assist along with the Baggage; I put myself in an Indian walking Dress.” (Journal of Major George Washington, 1754. Page 20)

When getting in or out of a canoe (the major mode of travel at the time), leggings can be removed to avoid getting them wet and if they are made of wool, dry quickly when they do get wet.

Indian dress became the norm for the Canadien at war as well. By the 1740s, breechcloths and leggings became issued dress to miliciens (militiamen) with the Indian’s deer/moose hide moccasins replaced by the soulier de boeuf or “oxhide” shoe. The SdB is a combination of a vamped moccasin design and the tanned cowhide of the European shoe.

“1 breechcloth, 1 pair of leggings”

(List of supplies issued to Canadian militia by Bourlamaque. National Archives of Canada, MG-18, K-9, Papiers Bourlamaque, Volume 6, 2e partie (1756-1760))

“The six canadiens receive the following…6 pairs of oxhide shoes.” (Supplies for the expedition led by the Chevalier de Niverville, 1747. Archives des colonies, series C11A, volume 117.)

Deerskins (and sometimes deerskin moccasins) were, however, issued for winter campaigns for use in making moccasins compatible with snowshoes.

“2 pairs deerskin moccasins, one dressed deerskin” (Bougainville. Winter expedition issue. Page 87)

“2 pairs of deerskin moccasins, 1 dressed deerskin and no tanned shoes” (List of supplies issued to Canadian militia by Bourlamaque. National Archives of Canada, MG-18, K-9, Papiers Bourlamaque, Volume 6, 2e partie, 1756-1760)

In my personal opinion, Indian dress is the best thing going! It is cheap (an important factor for the new re-enactor/living historian in these leaner times), easy to make, affords a freedom of movement unknown to our friend who wear wool regimentals and in NY’s muggy summers, it keeps you much cooler.

I often feel bad for my friends who portray Provincial and Regular soldiers at events like Fort Ticonderoga’s “Clash of Empires”. The event (held the last weekend in June) is notoriously hot and muggy and watching those guys wear wool waistcoats and a wool coat hurts ME. The civilians don’t have it much better. While I can walk about in my shirt, moccasins and breechcloth, they wear coats and waistcoats and breeches. Yes, they can be made of lighter material like linen, but the effect of multiple layers is the same.

To be continued...

While researching Canadien milice (militia) and the Fur Trade during the 17th and 18th centuries, one thing is quite evident. The French-Canadian was on much better terms with his red-skinned neighbors than the English settler to the south. One big factor was the difference in philosophy. The English, by and large, came to the New World to settle, grow crops and harvest timber, etc. They sought ownership of land. The French had minimal settlement. They were after furs and cod to send home more than anything else, keeping only as many settlers as needed to support these 2 industries.

Swedish scientist Peter Kalm traveled to New York and New France in the late 1740s. His journals are invaluable to the modern living historian. For students of 18th century New France, Kalm’s journals give us a glimpse of life among the upper class as well as commoner. For my purposes, the descriptions of the average Canadien at home and in travels in the forest are the focus.

Kalm mentions on multiple occasions the similarities in dress between the French and the Indians:

"Though many nations imitate the French customs, I observed on the contrary, that the French in Canada in many respects follow the customs of the Indians, with whom they have constant relations. They use the tobacco pipes, shoes, garters, and girdles of the Indians. They follow the Indian way of waging war exactly; they mix the same things with tobacco; they make use of the Indian bark boats and row them in the Indian way; they wrap a square piece of cloth around their feet [as a moccasin liner], instead of stockings, and have adopted many Indian fashions.” (Kalm, page 511)

“During the week the men went about in their homes dressed much like the Indians, namely, in stockings and shoes like theirs, with garters, and a girdle about the waist; otherwise the clothing was like that of other Frenchmen.” (Kalm, page 558)

“From the skins of these animals [deer] the natives as well as the French in -Canada make their shoes which they use on their journeys…” (Kalm, page 589)

The wearing of breechcloth and leggings was not just an 18th century phenomenon. The coureur de bois had figured out the advantages to this form of dress many years before:

“They [the CdB] easily adopt Indian fashions. They run the woods with leggings and moccasins and instead of breeches they wear only a breechclout.” (H. de Tonty, Dernieres decouverts dans l’Amerique Septentrionale de M. de La Salle, Paris, 1697. Page 14)

Gov. Denonville wrote of woodsmen who “put themselves in Indian Dress” in 1685. (Archives Nationales de Canada, C11A, volume 7, folio 90)

By the middle of the next century, Indian dress was the norm for the Canadien in the forest.

“When the French are traveling about in this country, they are generally dressed like the natives; they wear no trousers…” (Kalm Page 560)

The term “Indian Dress” in the 18th century generally meant shirt, breechcloth and leggings. It is a simple, inexpensive dress (even today!) that afforded relative comfort and freedom of movement. Even George Washington saw its merits.

“I wou'd not only order the Men to adopt the Indian dress, but cause the Officers to do it also, and be the first to set the example myself. Nothing but the uncertainty of its taking with the General causes me to hesitate a moment at leaving my Regimentals at this place, and proceeding as light as any Indian in the Woods. 'Tis an unbecoming dress, I confess, for an officer; but convenience rather than shew, I think shou'd be consulted. The reduction of Bat Horses alone, is sufficient to recommend it; for nothing is more certain than that less baggage will be requir'd, and that the Publick will be benifitted in proportion." (Washington to Col. Bouquet; Camp near Fort Cumberland, July 3, 1758.)

“…therefore myself and others gave up our horses for Packs, to assist along with the Baggage; I put myself in an Indian walking Dress.” (Journal of Major George Washington, 1754. Page 20)

When getting in or out of a canoe (the major mode of travel at the time), leggings can be removed to avoid getting them wet and if they are made of wool, dry quickly when they do get wet.

Indian dress became the norm for the Canadien at war as well. By the 1740s, breechcloths and leggings became issued dress to miliciens (militiamen) with the Indian’s deer/moose hide moccasins replaced by the soulier de boeuf or “oxhide” shoe. The SdB is a combination of a vamped moccasin design and the tanned cowhide of the European shoe.

“1 breechcloth, 1 pair of leggings”

(List of supplies issued to Canadian militia by Bourlamaque. National Archives of Canada, MG-18, K-9, Papiers Bourlamaque, Volume 6, 2e partie (1756-1760))

“The six canadiens receive the following…6 pairs of oxhide shoes.” (Supplies for the expedition led by the Chevalier de Niverville, 1747. Archives des colonies, series C11A, volume 117.)

Deerskins (and sometimes deerskin moccasins) were, however, issued for winter campaigns for use in making moccasins compatible with snowshoes.

“2 pairs deerskin moccasins, one dressed deerskin” (Bougainville. Winter expedition issue. Page 87)

“2 pairs of deerskin moccasins, 1 dressed deerskin and no tanned shoes” (List of supplies issued to Canadian militia by Bourlamaque. National Archives of Canada, MG-18, K-9, Papiers Bourlamaque, Volume 6, 2e partie, 1756-1760)

In my personal opinion, Indian dress is the best thing going! It is cheap (an important factor for the new re-enactor/living historian in these leaner times), easy to make, affords a freedom of movement unknown to our friend who wear wool regimentals and in NY’s muggy summers, it keeps you much cooler.

I often feel bad for my friends who portray Provincial and Regular soldiers at events like Fort Ticonderoga’s “Clash of Empires”. The event (held the last weekend in June) is notoriously hot and muggy and watching those guys wear wool waistcoats and a wool coat hurts ME. The civilians don’t have it much better. While I can walk about in my shirt, moccasins and breechcloth, they wear coats and waistcoats and breeches. Yes, they can be made of lighter material like linen, but the effect of multiple layers is the same.

To be continued...

Saturday, March 19, 2011

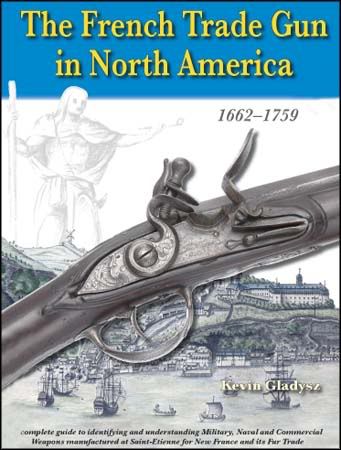

Book Review: "The French Trade Gun in North America: 1662-1759 by Kevin Gladysz

Folks on the French side of the hobby have been waiting for this one for quite a while. I just received my copy yesterday and I must say I'm impressed.

Ever read something so full of information that it's difficult to absorb any of it? Or see so many illustrations that you find yourself skipping ahead to look at them and read the captions? That's what I've been dealing with...

There are excellent illustrations, pictures of guns from various collections and quotes from tons of primary sources. This is a MUST READ for anyone portraying a milicien or sauvage in New France, Acadia or Louisiana during the period.

But be prepared. You'll want a new fusil from St. Etienne soon after opening this book...

You've been warned.

Thursday, March 3, 2011

Lessons Sam Hearne taught me... Part 1

Samuel Hearne is not a name you hear often these days. As a matter of fact, I stumbled across his name purely by accident. Born in 1745 he joined the Nay during the French and Indian War and signed on with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1766. His biggest claim to fame is being the first European to traverse the Arctic/sub-Arctic region west of Hudson’s Bay, all the way to the Arctic Ocean. He also brought a new method of travel to the forefront. Peter Newman put it well: “He pioneered a new technique of exploration- the propensity to go native.”

It took Hearne 3 attempts to accomplish his mission. The first 2 times, he was governed by a very European way of thinking. Haul all the provisions you need. Travel without any women along. Both theories caused him to turn back. It is impossible to carry sufficient provision for a journey of this duration. One must live mostly off the land. Women (from the Cree and Athabaskan tribes) were indispensable. They helped in camp and processed the hides and furs the men procured so that they could be utilized to replace worn out clothing.

Having traveled in the sub-Arctic forest and tundra my years in Alaska, I have a very good idea what Hearne and his guides went through. I wish I had found out about him earlier. What follows will be some tips & techniques I came across reading his journal, A Journey to the Northern Ocean.

Guns for the Traveling Man

“It is, however, rather dangerous firing lumps of iron out of such slight barrels as are brought to this part of the world for trade. These, though light and handy, and of course well adapted for the use of both English and Indian in long journies, and of sufficient strength for leaden shot or ball, are not strong enough for this kind of shot…”

November 1st, 1770. pg 50

Any student of trade guns of the 18th century does not see this as a shock. Although, Hearne's recommendation for one for Englishmen is telling.

He continues:

“…and strong fowling-pieces would not only be too heavy for the laborious ways of hunting in this country, but their bores being so much larger, would require more than double the quantity of ammunition that small ones do; which, to Indians, must be an object of no inconsiderable importance.”

Hunters and warriors from Athabaskans to Seminoles wanted light guns. Easier to carry, used lighter weight ammunition (a costly item in the Far North). We see this throughout the colonies as well. Sir William Johnson of NY sent back guns that he deemed to wide in the bore, because the Iroquois wouldn't buy them.

Currently, my main firelock is a Carolina Gun/Type G made by Mike Brooks of Iowa. It follows the description of an order for Sir William:

“400 Indian Fusees London provd blue Barrels Walnut stocks polishd Locks Brass Furniture 16/320”

Inventory of Sundry Merchandise…, London 5 Sept 1770

SWJP Vol VII, pg 885-888

It is also very close in style and weight to the Bumford Trade Gun in the collection of Colonial Williamsburg. (see Mullins, Jim "Of Sorts For Provincials" or Gale, Ryan "For Trade and Treaty"). Bumford also was a supplier of fowling guns to the HBC, Hearne's company. There is no direct evidence that puts this exact type at Prince of Wales Fort (Hearne's base), but it would make sense.

Anyhow, at 6lbs 2oz, I can carry it all day. It's balance keeps the 48" barrel from seeming unwieldy. Looking back to my time in Alaska, it would have worked well.

Traveling Light

"...but as to myself, little was required to be done, as the nature of travelling long journies in those countries will never admit of carrying even the most common article of clothing; so that the traveller is obliged to depend on the country he passes through for that article, as well as for provisions. Ammunition, useful iron-work, some tobacco, a few knives, and other indispensable articles, make a sufficient load for any one to carry that is going on a journey likely to last twenty months or two years. As that was the case, I only took the shirt and clothes I then had on, one spare coat, a pair of drawers, and as much cloth as would make me two or three pair of Indian stockings {leggings}, which together with a blanket for bedding, composed the whole of my stock of clothing." page 12.

And modern backpackers think THEY travel light???? This is the ultimate test in the belief of the "The more you carry in your head, the less you carry on your back" school of thought. By "iron-work", Hearne means ice-chisels (for getting through the multiple FEET of ice on the lakes and rivers), files for sharpening tools, knives, hatchets, and awls.

Basically, you take tools to build rather than the items themselves. Build the canoe, snowshoes, etc as you need them. Travel light and move faster. I wish I had come to believe in this method when I was in Alaska. There was a fairly large pool of knowledge among the elders of the Athabaskan villages. Sadly, most of the younger generation doesn't care and the elders are passing away every day.

Duplicating this journey with only the few things they took would be the ULTIMATE scout for the Historical Trekker. Let's see if "Out of the Wild" picks this one up next season...

Thursday, February 10, 2011

Jan 2011 Snowshoe scout

Went and checked out a small piece of State Forest by my place. My friends Snapper and Suzanne came along since they had a day off from work. It had been a while since I had taken my snowshoes out and felt great to put them on again. Other than having to adjust the bindings a few times, all went well.

I used my basic winter gear: Linen shirt, wool breechcloth, wool leggings, wool waistcoat, wool stockings, wool nippes (pieces of cloth wrapped around the foot) and moosehide mocassins all covered up with my 1750s wool capote (can you tell I like wool?).

I carried my wool Monmouth cap but only used it about 1/2 the time. I also took my Type G trade gun, a fire bag, powder horn, slit pouch with shooting supplies, a tumpline and blanket roll (with a hatchet, some honey cakes, kettle and cup attached). The #1 lesson I learned on this short jaunt? I need to figure out a better way to carry the kettle...

During the lulls in conversation, I thought often of those who traveled like this because of the need instead of the want. We do it because it's cool. They did it because there was no other choice.

In this blog, my main focus will be the First Nations of the Northeast US, Canada and Alaska as well as those of European ancestry (mostly French-Canadian) who ventured out by canoe and snowshoe in connection with the Fur Trade. This is dedicated to them.

I used my basic winter gear: Linen shirt, wool breechcloth, wool leggings, wool waistcoat, wool stockings, wool nippes (pieces of cloth wrapped around the foot) and moosehide mocassins all covered up with my 1750s wool capote (can you tell I like wool?).

I carried my wool Monmouth cap but only used it about 1/2 the time. I also took my Type G trade gun, a fire bag, powder horn, slit pouch with shooting supplies, a tumpline and blanket roll (with a hatchet, some honey cakes, kettle and cup attached). The #1 lesson I learned on this short jaunt? I need to figure out a better way to carry the kettle...

During the lulls in conversation, I thought often of those who traveled like this because of the need instead of the want. We do it because it's cool. They did it because there was no other choice.

In this blog, my main focus will be the First Nations of the Northeast US, Canada and Alaska as well as those of European ancestry (mostly French-Canadian) who ventured out by canoe and snowshoe in connection with the Fur Trade. This is dedicated to them.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)